Vaccines, Liberty and John Stuart Mill's Harm Principle

Unless you have been living on Mars, you may have noticed the two ongoing political disputes that give opposing answers to questions about the limits of individual liberty. The first question is whether social media outlets (like Facebook) should be legally required to prohibit posts that give false or misleading information about vaccines developed to immunize the human body from COVUD-19 The second question is about requiring certain groups of people to be vaccinated, for example, teachers, college students, school children, government employees, workers in businesses with more than 25 employees.

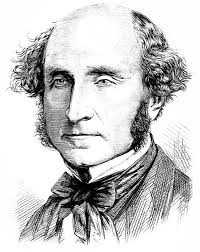

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) was an advocate of an ethical theory called Utilitarianism. The theory said that moral rules should be grounded in utility, meaning that the rules should require conduct that promotes the greatest happiness for the greatest number. Thus, we have rules requiring that people tell the truth and keep their promises because conformity to these rules in society promotes the greatest happiness. This does not mean that the rules are absolute. Of course, there will be exceptions, but the exceptions must be tested by utility. You would be justified in telling a lie to a crazed man holding a knife or gun if he asked you where his former wife was hiding.

In his book On Liberty, Mill promoted a utilitarian-based principle called "harm-to-others". Mill distinguished between conduct that causes harm only to oneself and conduct that causes (or threatens to cause) harm to others. If a lonely alcoholic drinks only in his home then he harms only himself. If he drives a car and hits another occupied car while drunk, injuring himself and the people inside the car, then his conduct causes harm not only to himself but to others.

The harm principle implies that he has a right to get drunk in his home but only if he stays there and does not threaten harm to others. Although the drunken man might be unhappy because he cannot drive while drunk, the happiness of sober drivers is far greater than his unhappiness.

The harm principle easily applies to the details of the COVID-19 vaccine dispute. Unvaccinated people who refuse vaccination threaten the health and even the life of others if they insist on leaving their house and mingling with others in large crowds where there might be unvaccinated or vulnerable vaccinated people, especially the elderly and very young children. The latter persons have a right not to be harmed. The unvaccinated persons have no utilitarian right to harm them or put them at risk of being harmed. They can risk their own death by refusing vaccination but they cannot risk causing others to die or become ill.

The harm principle can also be used to settle the question of whether children should be required to wear face masks or to get vaccinated as a condition of going to in-person classrooms. Parents have no moral or legal right to endanger their own children nor do they have the right to endanger the health of other children in the classroom by sending them to school without a mask. The harm-to-others principle trumps parental rights. If parents must get their children vaccinated for measles and mumps, then there is a similar good reason why they should be vaccinated for covid-19. The COVID-19 virus causes as much or more damage than measles and mumps.

This takes us to the second question that Mill implicitly answers in On Liberty. It is about freedom of speech. Should social media posts about the safety of vaccinations for COVID-19 be prohibited by law if the posts are false or misleading? For example, a rumor on social media was recently spread saying that the vaccine can affect a woman's fertility.(https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/coronavirus/covid-19-vaccines-myth-versus-fact). Other rumors have claimed that the vaccine will kill all those who take it! Should rumors such as these be barred from publication?

In On Liberty, Mill argues that the expression of an opinion is justifiably prohibited by law only if the expression causes or would cause harm to others. Examples of such expressions are libel, slander, and incitement to riot. Examples of opinions that are false, misleading, or unsupported by evidence but cause no harm to others who hear or read these opinions cannot be justifiably suppressed.

It might be objected that

people who hear false opinions sometimes take them seriously and act on them in

a way that causes them harm. For example, President Biden recently

complained that thousands of Americans have died of COVID-19 because they had

believed and acted on the false opinion that the vaccines offered to prevent

infection would kill them. Is this a sufficient reason for prohibiting social media posts that spread lies about getting vaccinated?

The objection fails to take into account a distinction between immediate and mediate harm. If person A slanders the reputation of person B, then B has been immediately harmed by A's slanderous speech. B had no control over the slander. But if A writes a social media post saying that anti-COVID vaccines will kill people, then no particular person, including B, has been targeted by A. Second, if B reads and believes A's post, refuses to take the vaccine, eventually contracts COVID-19 and dies, B is harmed but not immediately harmed. The harm is mediate because B voluntarily acted on A's opinion. B was presented with A's opinion and it was up to B to determine whether it was true or false. To put it another way, the causal links between A’s social media post and B’s death was B’s accepting as true the false claim that the vaccine would kill him, and B’s subsequent refusal to be vaccinated. Although we might say “But for A’s lie, B would not have died,” we can also say “But for believing A’s lie, B would not have died.” Third, if B fails to investigate the veracity of the opinion and acts on it in a way that leads to his death, then we would not conclude that "A killed him," nor would we conclude that A killed all those who read his social media post, acted on it and eventually died of the virus.

This leads to Mill's famous remark that "the peculiar evil of silencing of an opinion is that it is robbing the human race." The robbery Mill has in mind is being deprived of the opportunity to "exchange error for truth." We cannot just assume that what we think about the safety of vaccines is true and what others think must be false. We need to hear the opinions of others, no matter how ridiculous these opinions might sound to us. For all we know, there is at least a logical possibility that they might be right! On the other hand, if their opinions are wrong, then we lose "what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth produced by its collision with error."

Mill has given us the utilitarian task of balancing good and bad consequences. The mediate but good consequences of prohibiting posts of false and misleading opinions about the safety of anti-COVID vaccines is that more people will take the vaccine, the spread of the disease will be limited, and fewer people will die. The bad consequence is that such prohibitions on speech will damage our "mental well-being" and "self-improvement" by being robbed of the opportunity to challenge opinions that the silencers of speech think might be false. Mill would warn us that if we silence speech in cases like this (anti-vaccination rants on social media), then this opens the door to those who would silence any false or misleading speech that might lead to mediate harm.

For more about Mill's writings, read his books Utilitarianism and On Liberty. And if you need help reading these books, read my study guide: Understanding John Stuart Mill: The Smart Student's Guide to Utilitarianism and On Liberty.

No comments:

Post a Comment